POSTS

Dropout and the Deep Complexity of Neural Networks

There’s a common misconception that neural networks’ recent success on a slew of problems is due to the increasing speed and decreasing cost of GPUs. In reality, that’s not the case. Modern processing power plays a critical role, but only when combined with a series of innovations in architecture and training. You can’t process million-image datasets like ImageNet without a GPU, but without Resnet you won’t be able to achieve good results. Today’s deep learning results actually stem from a series of fairly simple innovations that yield huge improvements in the efficacy of using neural networks for machine learning problems. Today’s post is about “dropout”, one of those innovations. Dropout seems obvious in hindsight but it yields huge gains when training nearly all types of neural networks.1

Most of this post is targeted at people just getting their toes wet with deep learning – if you’re an experienced practitioner you may want to skip to Dropout in 2018 which discusses the current state-of-the-art.

The World Before Dropout

First, a quick primer on how neural networks work, feel free to skip ahead. At their core, neural networks are built on simple pieces. Most modern neural network networks are composed of linear functions, \(ax+b\), and “activations” \(\max(0, x)\). When people talk about “weights”, they’re referring to \(a\) and \(b\) in \(ax+b\).

Above is an incredibly simple neural network architecture, capable of learning simple regressions. It contains a “fully connected linear layer” followed by an activation. The training phase involves examining each of the weights in turn and determining how a small change to the weight impacts the output. Given this information, it makes a small adjustment to all of the weights to bring the actual output of the neural network closer to the target. Doing this for millions of weights simultaneously, on vectors instead of scalars requires vector calculus (the “hard math” part of deep learning) but the core concept is the same. For a longer intro with a bit more detail, Jay Allamar’s post is a good resource.2

Compared to many other machine learning methods, neural networks have a massive number of free parameters. Typical architectures for image classification have 10-100 million free parameters.3 With so many free parameters, neural networks have a tendency to overfit the training data. Overfitting is essentially equivalent to memorizing the training set instead learning its patterns. Just like non-artificial learning, memorization is of limited utility if you need to be able to handle things you’ve never seen before. Overfitting is especially prevalent when training large, fully connected layers because so many weights are being altered simultaneously. Ideally, there would be a way to train a neural network in a way that prevented it from overfitting.

Enter Dropout

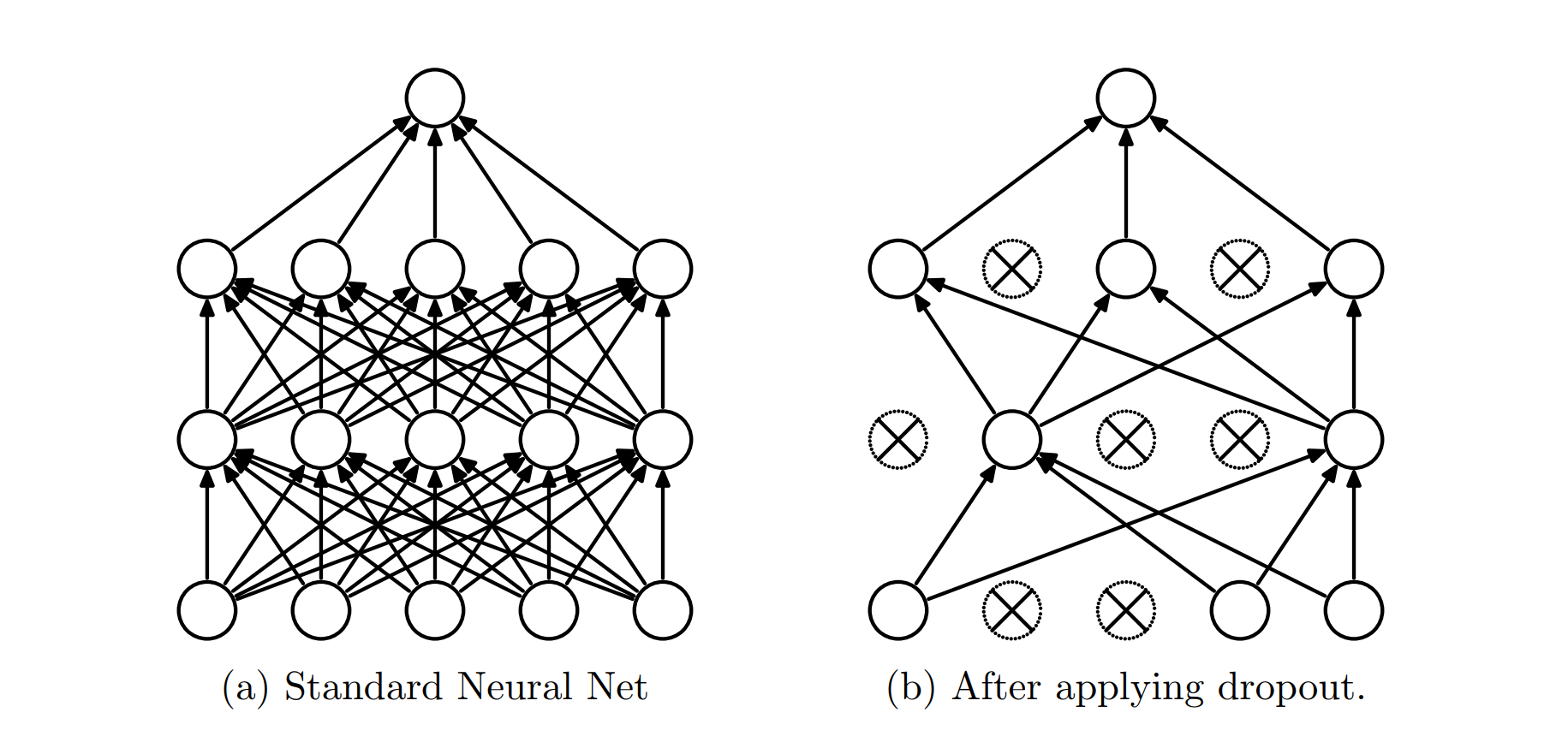

Developed by Nitish Srivastava, Geoffrey Hinton, et al. in 2013, dropout was one of the first generally applicable techniques to combat overfitting when training neural networks. Dropout is simply ignoring, at random, the results of some neurons in the network each time you train a minibatch (subset) of your data. When we evaluate our performance on the validation data, we don’t ignore any nodes. There is one wrinkle: Suppose we randomly ignore the output of \(\frac{1}{2}\) of the nodes. On average, the total output of the layer will be 50% less, confounding the neural network when running without dropout. Luckily, neural networks just sum results coming into each node. To compensate for dropout, we can multiply the outputs at each layer by 2x to compensate. This process is known as re-scaling. For more details on the nitty gritty and the original performance results, see the original paper.

Image from Srivastava et al 2014

Beyond simply preventing overfitting, dropout can be thought of as training an ensemble of neural networks whose final results are averaged at test time.4 Although dropout isn’t a panacea for overfitting, it does lead to significant improvements.

Dropout in 2018

Dropout was a big step forward when it was originally proposed resulting in new state-of-the-art results on many machine vision problems. In combination with batch normalization, dropout is still the goto technique for training fully connected layers. In computer vision, however, the convolutional kernels used by most models have a much smaller number of parameters per layer, rendering dropout less effective. Most models like ResNet are using batch normalization instead.5 However, the recent work of Sergey Zagoruyko, Nikos Komodakis (2017) experiments with a wider version of Resnet and seems to show that dropout can still be effective in convolution architectures.6 For NLP problems, ULMFiT, a state of the art NLP model based on AWD-LSTM uses dropout between the layer groups.

Since the original dropout paper, there have been several attempts to improve upon the initial dropout strategy. Dropout++ makes the dropout weight a trainable parameter.7 “Generalized Dropout” suggests withholding a subset of the training data (eg. setting certain pixels to black) rather than disabling neurons – essentially a form of data augmentation that adds random noise.8 “Dropout distillation” frames traditional dropout as the creation of an ensemble of individual models (all of which share the same weights). While traditional dropout blindly “averages” the results of these submodels (via rescaling), “dropout distillation” attempts to learn how to weight the final ensemble via SGD.9 Even with several proposed dropout improvments, to my knowledge, none have made it to the mainstream.

Closing Thoughts

Dropout is counter intuitive – to learn best, we need to continuously forget some of what we learned. Even though dropout is an incredibly simple technique developed four years ago, there isn’t a single conclusive explanation of its effectiveness.10 Even as we understand neural networks better, their complexity and depth evade simple explanations. Dropout seems to be most effective on layers with a large number of parameters, but if you’re working on a new architecture or tweaking an existing one, it’s probably worth trying.

Want to get emailed about new blog posts?

Do you want to hire me? I’m available for engagements from 1 week to a few months. Hire me!

- Dropout made a big difference across the board when it was introduced because other modern techniques had yet to be developed. Other techniques like batch normalization have replaced it in certain cases today. [return]

- It’s important to call out that neural networks in 2018 aren’t just fully connected linear layers like the picture. Vision based neural networks are based on convolutional kernels. Networks for learning longer sequences of data like language use “recurrent neural networks” or more recently “attention networks”. [return]

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1702.08782.pdf, page 5 [return]

- The “ensemble” interpretation of dropout was proposed in the original paper, and was used as the inspiration for several follow on papers. [return]

- The standard Resnet uses batch normalization prior to the ReLU instead of dropout: https://towardsdatascience.com/an-overview-of-resnet-and-its-variants-5281e2f56035 [return]

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1605.07146.pdf Zagoruyko and Komodakis propose a much wider Resnet block. Their new, wider, Resnet block introduces significantly more parameters per layer – as such, they return to the original purpose of dropout, to prevent overfitting in layers with 1000s of parameters. [return]

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1611.06791.pdf [return]

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.00891.pdf [return]

- http://proceedings.mlr.press/v48/bulo16.pdf [return]

- http://proceedings.mlr.press/v48/bulo16.pdf cites 6 different papers attempting to explain the effectiveness of dropout. [return]