POSTS

My Favorite Algorithm: Linear Time Median Finding

Finding the median in a list seems like a trivial problem, but doing so in linear time turns out to be tricky. In this post I’m going to walk through one of my favorite algorithms, the median-of-medians approach to find the median of a list in deterministic linear time. Although proving that this algorithm runs in linear time is a bit tricky, this post is targeted at readers with only a basic level of algorithmic analysis.

Finding the median in O(n log n)

The most straightforward way to find the median is to sort the list and just pick the median by its index. The fastest comparison-based sort is \(O(n \log n)\), so that dominates the runtime.12

def nlogn_median(l):

l = sorted(l)

if len(l) % 2 == 1:

return l[len(l) / 2]

else:

return 0.5 * (l[len(l) / 2 - 1] + l[len(l) / 2])Although this method offers the simplest code, it’s certainly not the fastest.

Finding the median in average O(n)

Our next step will be to usually find the median within linear time, assuming we don’t get unlucky. This algorithm, called “quickselect”, was devevloped by Tony Hoare who also invented the similarly-named quicksort. It’s a recursive algorithm that can find any element (not just the median).

- Pick an index in the list. It doesn’t matter how you pick it, but choosing one at random works well in practice. The element at this index is called the pivot.

- Split the list into 2 groups:

- Elements less than or equal to the pivot,

lesser_els - Elements strictly greater than the pivot,

great_els

- Elements less than or equal to the pivot,

- We know that one of these groups contains the median. Suppose we’re looking for the kth element:

- If there are k or more elements in

lesser_els, recurse on listlesser_els, searching for the kth element. - If there are fewer than k elements in

lesser_els, recurse on listgreater_els. Instead of searching for k, we search fork-len(lesser_els).

- If there are k or more elements in

Here’s an example of the algorithm running on a list with 11 elements:

Consider the list below. We'd like to find the median.

l = [9,1,0,2,3,4,6,8,7,10,5]

len(l) == 11, so we're looking for the 6th smallest element

First, we must pick a pivot. We randomly select index 3.

The value at this index is 2.

Partitioning based on the pivot:

[1,0,2], [9,3,4,6,8,7,10,5]

We want the 6th element. 6-len(left) = 3, so we want

the third smallest element in the right array

We're now looking for third smallest element in the array below:

[9,3,4,6,8,7,10,5]

We pick an index at random to be our pivot.

We pick index 3, the value at which, l[3]=6

Partitioning based on the pivot:

[3,4,5,6] [9,7,10]

We want the 3rd smallest element, so we know it's the

3rd smallest element in the left array

We're now looking for the 3rd smallest in the array below:

[3,4,5,6]

We pick an index at random to be our pivot.

We pick index 1, the value at which, l[1]=4

Partitioning based on the pivot:

[3,4] [5,6]

We're looking for the item at index 3, so we know it's

the smallest in the right array.

We're now looking for the smallest element in the array below:

[5,6]

At this point, we can have a base case that chooses the larger

or smaller item based on the index.

We're looking for the smallest item, which is 5.

return 5

To find the median with quickselect, we’ll extract quickselect as a separate function. Our quickselect_median function will call quickselect with the correct indices.

import random

def quickselect_median(l, pivot_fn=random.choice):

if len(l) % 2 == 1:

return quickselect(l, len(l) // 2, pivot_fn)

else:

return 0.5 * (quickselect(l, len(l) / 2 - 1, pivot_fn) +

quickselect(l, len(l) / 2, pivot_fn))

def quickselect(l, k, pivot_fn):

"""

Select the kth element in l (0 based)

:param l: List of numerics

:param k: Index

:param pivot_fn: Function to choose a pivot, defaults to random.choice

:return: The kth element of l

"""

if len(l) == 1:

assert k == 0

return l[0]

pivot = pivot_fn(l)

lows = [el for el in l if el < pivot]

highs = [el for el in l if el > pivot]

pivots = [el for el in l if el == pivot]

if k < len(lows):

return quickselect(lows, k, pivot_fn)

elif k < len(lows) + len(pivots):

# We got lucky and guessed the median

return pivots[0]

else:

return quickselect(highs, k - len(lows) - len(pivots), pivot_fn)Quickselect excels in the real world: It has almost no overhead and operates in average \(O(n)\). Let’s prove it.

Proof of Average O(n)

On average, the pivot will split the list into 2 approximately equal-sized pieces. Therefore, each subsequent recursion operates on 1⁄2 the data of the previous step.

$$C=n+\frac{n}{2}+\frac{n}{4}+\frac{n}{8}+…=2n=O(n)$$

There are many ways to prove that this series converges to 2n. Rather than reproducing one here, I’ll just direct you to the excellent Wikipedia article about this specific infinite series.

Quickselect gets us linear performance, but only in the average case. What if we aren’t happy to be average, but instead want to guarantee that our algorithm is linear time, no matter what?

Deterministic O(n)

In the section above, I described quickselect, an algorithm with average \(O(n)\) performance. Average in this context means that, on average, the algorithm will run in \(O(n)\). Technically, you could get extremely unlucky: at each step, you could pick the largest element as your pivot. Each step would only remove one element from the list and you’d actually have \(O(n^2)\) performance instead of \(O(n)\).

With that in mind, what follows is an algorithm for picking pivots. Our goal will be to pick a pivot in linear time that removes enough elements in the worst case to provide \(O(n)\) performance when used with quickselect. This algorithm was originally developed in 1973 by the mouthful of Blum, Floyd, Pratt, Rivest, and Tarjan. If my treatment is unsatisfying, their 1973 paper will certainly be sufficient. Rather than walk through the algorithm in prose, I’ve heavily annotated my Python

implementation below:

def pick_pivot(l):

"""

Pick a good pivot within l, a list of numbers

This algorithm runs in O(n) time.

"""

assert len(l) > 0

# If there are < 5 items, just return the median

if len(l) < 5:

# In this case, we fall back on the first median function we wrote.

# Since we only run this on a list of 5 or fewer items, it doesn't

# depend on the length of the input and can be considered constant

# time.

return nlogn_median(l)

# First, we'll split `l` into groups of 5 items. O(n)

chunks = chunked(l, 5)

# For simplicity, we can drop any chunks that aren't full. O(n)

full_chunks = [chunk for chunk in chunks if len(chunk) == 5]

# Next, we sort each chunk. Each group is a fixed length, so each sort

# takes constant time. Since we have n/5 chunks, this operation

# is also O(n)

sorted_groups = [sorted(chunk) for chunk in full_chunks]

# The median of each chunk is at index 2

medians = [chunk[2] for chunk in sorted_groups]

# It's a bit circular, but I'm about to prove that finding

# the median of a list can be done in provably O(n).

# Finding the median of a list of length n/5 is a subproblem of size n/5

# and this recursive call will be accounted for in our analysis.

# We pass pick_pivot, our current function, as the pivot builder to

# quickselect. O(n)

median_of_medians = quickselect_median(medians, pick_pivot)

return median_of_medians

def chunked(l, chunk_size):

"""Split list `l` it to chunks of `chunk_size` elements."""

return [l[i:i + chunk_size] for i in range(0, len(l), chunk_size)]Let’s prove why the median-of-medians is a good pivot. To help, consider this visualization of our pivot-selection algorithm:

The red oval denotes the medians of the chunks, and the center circle denotes the median-of-medians. Recall that we want our pivot to split the list as evenly as possible. Let’s consider the worst possible case – the case where are pivot is as close as possible to the beginning of the list (without loss of generality, this argument symmetrically applies to the end of the list as well.)

Consider the four quadrants (which overlap, including the center column (when the number of columns is odd) & middle row):

- Top left: Every item in this quadrant is strictly less than the median

- Bottom left: These items may be bigger (or smaller!) than the median

- Top right: These items may be bigger (or smaller!) than the median

- Bottom right: Every item in this quadrant is strictly greater than the median

Out of these four two quadrants are useful because they allow us to make assertions about their contents (top left, bottom right) and two are not (bottom left, top right).

Now lets return to our original task, finding the worst possible case where our pivot falls as early in the list as possible. As I argued above, at a minimum, every item in the top left is strictly less than our pivot. How many items are there as a function of \(n\)? Each column has 5 items, of which we’ll take 3; we’re taking half of the columns, thus:

$$f(n)=\frac{3}{5}*\frac{1}{2}n=\frac{3}{10}n$$

Therefore, at each step, at minimum, we will remove, at minimum, 30% of the rows.

But is dropping 30% of the elements at each step sufficient? It’s worse than the 50% we achieved in the randomized algorithm. At each step, our algorithm must do:

- O(n) work to partition the elements

- Solve 1 subproblem 1⁄5 the size of the original to compute the median of medians

- Solve 1 subproblem 7⁄10 the size of the original as the recursive step

This yields the following equation for the total runtime, \(T(n)\):

$$T(n)=n + T\left(\frac{n}{5}\right)+T\left(\frac{7n}{10}\right)$$

It’s not straightforward to prove why this is \(O(n)\). The initial version of this post alluded to the master theorem, but someone recently brought to my attention that that is incorrect – since there are two recursive terms, you can’t apply the master theorem. Rather, the only straightforward proof that I’m aware of is by induction.3

Recap

We have quickselect, an algorithm that can find the median in linear time given a sufficiently good pivot. We have our median-of-medians algorithm, an \(O(n)\) algorithm to select a pivot (which is good enough for quickselect). Combining the two, we have an algorithm to find the median (or the nth element of a list) in linear time!

Linear Time Medians In Practice

In the real world, selecting a pivot at random is almost always sufficient. Although the median-of-medians approach is still linear time, it just takes too long to compute in practice. The C++ standard library uses an algorithm called introselect which utilizes a combination of heapselect and quickselect and has an \(O(n \log n)\) bound. Introselect allows you to use a generally fast algorithm with a poor upper bound in combination with an algorithm that is slower in practice but has a good upper bound. Implementations start with the fast algorithm, but fall back to the slower algorithm if they’re unable to pick effective pivots.

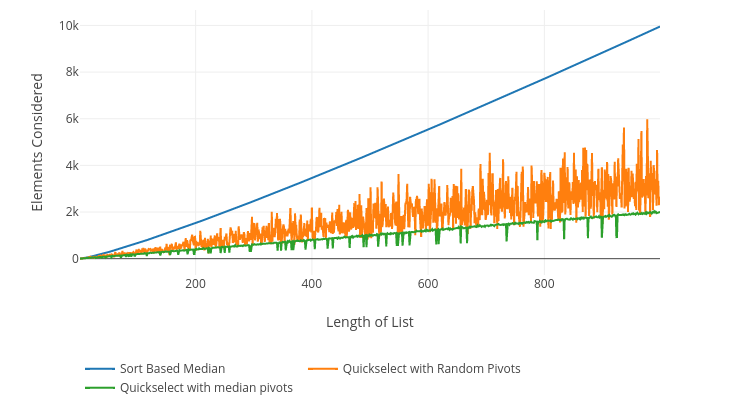

To finish out, here’s a comparison of the elements considered by each implementation. This isn’t runtime performance, but instead the total number of elements looked at by the quickselect function. It doesn’t count the work to compute the median-of-medians. The point of this graph is not to demonstrate that median-of-medians is a good algorithm, but rather to demonstrate that it’s an effective way to pick pivots.

It’s exactly what you would expect! The deterministic pivot almost always considers fewer elements in quickselect than the random pivot. Sometimes we get lucky and guess the pivot on the first try, which manifests itself as dips in the green line. Math works!

P.S: In 2017 a new paper came out that actually makes the median-of-medians approach competitive with other selection algorithms. Thanks to the paper’s author, Andrei Alexandrescu for bringing it to my attention!

Thanks to Leah Alpert for reading drafts of this post. Reddit users axjv and linkazoid pointed out that 9 mysteriously disappeared in my example which has since been fixed. Another astute reader pointed out several errors which have since been resolved:

- The recurrence relation was

\(7T(n/10)\)but should have been\(T(7n/10))\) - The master theorem is actually inapplicable in this case

- I incorrectly referred to the top right, instead of top left quadrant in my arguments

Want to get emailed about new blog posts?

Do you want to hire me? I’m available for engagements from 1 week to a few months. Hire me!

- This could be an interesting application of radix sort if you were attempting to find the median in a list of integers, all less than 2^32. [return]

- Python actually uses Timsort, an impressive combination of theoretical bounds and practical performance. Notes on Python Lists [return]

- See the final page of a lecture by Ron Rivest on the subject [return]