POSTS

Maximize Cache Performance with this One Weird Trick: An Introduction to Cache-Oblivious Data Structures

If you read my recent post about Postgres you may have noted that Postgres operates primarily with fixed-size blocks of memory called “pages.” By default, Postgres pages are 8KB. This number is tuned to match operating system page sizes which are tuned to match hardware cache sizes. If you were to run Postgres on hardware with different cache sizes than Postgres was tuned for, you may be able to pick a better page size.1

Along these lines, today’s post explores the question:

Can we design data structures and algorithms that perform optimally regardless of underlying cache sizes?

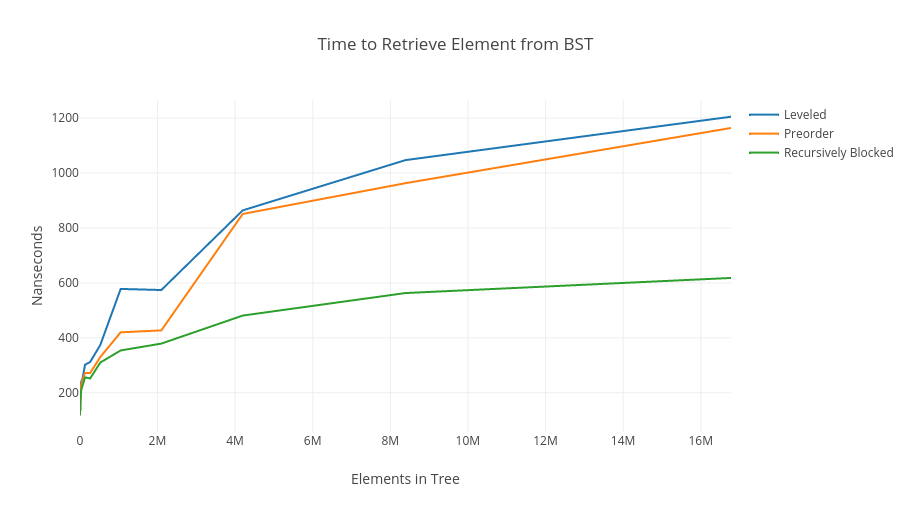

If we could do this, our code would optimally utilize all cache layers without tuning. In academia, algorithms and data structures that have these properties are referred to as cache-oblivious. (This is a pretty confusing name. A clearer name might be cache-size oblivious.) I find cache-oblivious data structures very satisfying because they can yield huge performance gains in practice. I’m going to skip to the punchline, a graph comparing the lookup performance of binary search trees:

The graph shows the time in nanoseconds to retrieve an element from a binary search tree vs. the number of elements in the tree. The series show 3 different ways of laying out the tree in memory.

- The blue line is a tree that’s been laid out level by level, essentially, a breadth first traversal of the tree.

- The orange line is a tree that’s been laid out in a preorder (depth first) traversal.

- The green line is a tree that’s been laid out with a so-called “recursive blocking” approach which is cache-oblivious. It is almost twice as fast for a tree with 16 million elements!

You can find the code I wrote to test out different strategies on Github. It’s written in Golang and utilizes their very helpful built in (!) benchmarking tools.

The rest of this post is dedicated to answering 2 questions:

- How is the green-line tree laid out in memory?

- Why is it so much faster?

If you want to know more about anything I’m talking about here, Erik Demaine’s 2002 survey paper covers the subject with far more rigor and detail than I’ll go into in this post.

A new scheme for analyzing algorithms

Big-O notation by itself can’t explain the differences we’re seeing. The code to search the trees is identical – the only difference is the order the nodes in the tree are laid out in memory.

In standard algorithmic analysis, we implicitly assume that the cost of reading from memory is directly proportional to amount of bytes we read. Read one byte, pay for one byte. But the real world doesn’t work this way: the layers of software and hardware below your programming language don’t work in individual bytes; they work in blocks.2 If you want to read one byte, you need to pay for the whole block. If you read more bytes from that block, those reads are nearly free. To analyze our algorithms, we’ll develop a model that’s closer to how things work in the real world.

In developing algorithms that perform optimally regardless of cache size, we’ll assume that we have 2 areas of memory: the small fast layer, and the big slow layer. Memory can only be moved from the slow layer to the fast layer in fixed size blocks of size \(B\). The slow layer is infinitely sized, and the fast layer has size \(M\).3 When we analyze our algorithms we’ll analyze them in terms of \(M\), the size of our cache, and \(B\), the size of blocks in the cache. Our analyses must hold for any values of \(M\) and \(B\). Futhermore, the unit of work we’ll be analyzing is loading a block from slow memory into fast memory – other work is considered much faster and not included.

Algorithms that make good use of the cache have the following very important property: When we read a block of data, we make use of every byte in that block. This property means that our algorithm will read fewer blocks as \(B\) increases.

Warm up: Finding the maximum in an array

A lot of algorithms are cache-oblivious without modification. Consider finding the maximum element in an array. Unless you’ve preprocessed the array in some way, you can’t do better than scanning the array and tracking the maximum. It’s pretty easy to see why this algorithm is cache optimal: Assuming the array is contiguous in memory, we’ll make use of every byte from every block we read, except for the ends. At each end if the array, we may make only partial use of 1 block on either end due to alignment.4

Binary Search Trees

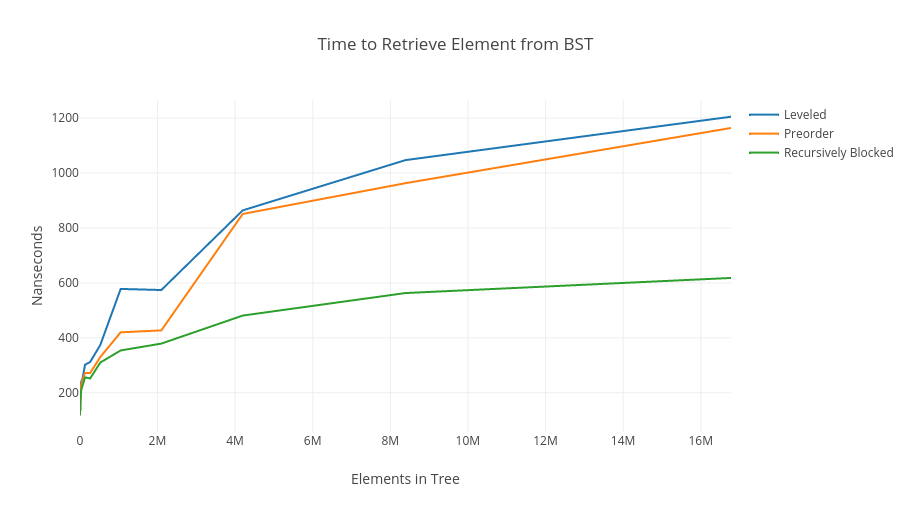

Onto the main event: Binary search trees. For ease of reference, here’s the graph from the intro again:

Looking at this graph, you can see that for small values of N, the performance doesn’t differ much. This because for small N, the layout doesn’t matter: the whole tree fits in one block! The weird flat spots in the graph are real and persist across many runs. They come from interaction with specific internal cache sizes. As N gets bigger, the differences between the slow and fast memory structures get larger and we eventually spill into main memory. The bigger the difference, the better the cache-oblivious version does.

Let’s dig into the ways we’ve laid these trees out in memory:

By Level (Breadth First)

This approach is the blue line in the graph. In the tree diagrams above and below, the numbers in the tree refer to the position the elements would lie in the array. The orange boxes show how the data is grouped in memory.

This is the “standard” way to layout a BST in memory that you have probably seen in textbooks. From a caching perspective, it’s one of the worst. It’s not too hard to see why:

If we’re traversing this tree from root to leaves, each row will be in a different block once the rows get large enough! We’ll only use 1 element we read from each block. Because of that, we’ll end up reading about \(\log_2N\) blocks.

Preorder (Depth First)

This approach is the orange line in the graph. it’s a bit better than the blue line, but pretty similar in the limit. This approach use what might be called a “depth-first” layout, proceeding down each branch before continuing on to the next one. As an aid, I’ve circled consescutive groups of 4 items within the tree to get an idea of the type of blocking behavior we’ll see. It’s easy to see these blocks are a little more useful than the breadth first approach. If we’re going down the far left branch, we’ll only have to read a single block. But it’s also easy to see the shortcomings: In a large tree, going down the far right branch will only use 1 item from each block.

Recursive Block Approach

This approach is the green line in the graph. In designing cache-oblivious data structures and algorithms, a divide and conquer strategy frequently bears fruit. This stems from the fact that divide and conquer algorithms naturally break the work in subproblems of increasingly smaller sizes – one of those sizes will be close to \(B\) and constrain the number of blocks you need to read. We’ll take a similar approach in laying our our cache-oblivious static BST.

To start, split the tree at half height. If the height of the tree is \(\log(N)\), the top section will contain \(2^{log_2(N)/2}=\sqrt{N}\) nodes. Each of the child nodes will also contain \(\approx \sqrt{N}\) elements. This splitting process is recursive – each section of the tree is split until there are no nodes left to split.

The figure above demonstrates a cache-oblivious memory layout for a binary search tree with 5 levels. The blocks are circled in green and the super-blocks are circled in orange. I’ve omitted the right branch to remove some visual clutter.

The key property of our layout strategy is that all “blocks” are laid out contiguously in memory. Critically, all “super blocks” are also contiguous. This means that no matter what \(B\) is, we’ll always be reading useful data. The key here is that the bigger the block you’re reading, the more levels you will go down the tree before needing to read an additional block. Specifically, if we read a block of size \(B\), we’ll be able to go \(\log_2B\) levels down the tree. The tree has \(\log_2N\) levels. This leads to the following result for what I’m calling \(F(N)\), the number of blocks read for a tree of size \(N\):

$$F(N)=\frac{\log_2N}{\log_2B}=\log_BN$$

I’m dropping some complexity in favor of simplicity; if this feels hand-wavy, you can find a more rigorous proof in the paper. Here’s the important part: as \(B\) grows, the number of blocks we read shrinks. Success!

Cache-Oblivious Data structures IRL

A static search tree isn’t really a general purpose data structure, but the ideas about recursively grouping data in memory are widely applicable. Beyond static BSTs, there are cache-oblivious sorting algorithms, hash tables, B-Trees, priority queues, and more. I won’t go into detail here, but you can read about them in Demaine’s survey paper. Cache-oblivious B-Trees are especially effective in practice. They are typically referred to as Fractal Tree Indexes. Given the fractal nature of cache oblivious BSTs, the name shouldn’t be a surprise. Tokutek, acquired by Percona in 2015, created cache-oblivious storage engines for several major databases with significantly improved performance. Personally, I find theory working out in practice especially satisfying.

Thanks to Leah Alpert for reading drafts of this post, suggesting structural refactorings, and suggesting that I include the leveled tree layout.

Want to get emailed about new blog posts?

Do you want to hire me? I’m available for engagements from 1 week to a few months. Hire me!

- One example is running Postgres on SSDs. For various reasons, SSDs to better with smaller block sizes: https://blog.pgaddict.com/posts/postgresql-on-ssd-4kb-or-8kB-pages [return]

- As you move from CPU caches (L1, L2, L3), to operating system level page caches, these blocks go from bytes in the L1 cache to kilobytes at the operating system level. [return]

To prove most cache-oblivious results, there are a number of assumptions required:

- The fast layer is a fully-associative cache (meaning it acts like a hash table; we can put any block anywhere). This isn’t how real CPU caches work. They are usually 2-8x associative. If a cache is N-way associative, then we have N different places in our cache this block is allowed to go. Fully associative means blocks can go anywhere, which just isn’t real. But we’ve got to start somewhere!

- We always evict the block that will be used as far as possible in the future (optimal eviction strategy)

- The cache is “tall” (much larger than the size of the blocks)

- A more rigorous proof: No matter how the blocks are split in the array, we’ll need to read at least

\(\frac{N}{B}\)blocks. In the worst case, both the first block and last block will contain exactly 1 element. This leads to\(\left \lfloor{\frac{N}{B}}\right \rfloor +2\)as the minimum number of blocks read by this algorithm, or,\(O(\left \lceil{\frac{N}{B}}\right \rceil)\). If we knew\(M\)and\(B\)ahead of time, we couldn’t possibly do better. [return]